Geographic atrophy, or GA eye disease, is an eye disease. It is a type of late-stage dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD). It impacts the central part of your eyesight, making it challenging to read, drive, or even recognize faces. If you or your family member has been diagnosed with geographic atrophy, or you are wondering "what is GA", this guide will walk you through all you need to know. We'll cover geographic atrophy, its symptoms, causes, risk factors, diagnosis, treatments, and what to do to lower your GA risk.

What is Geographic Atrophy?

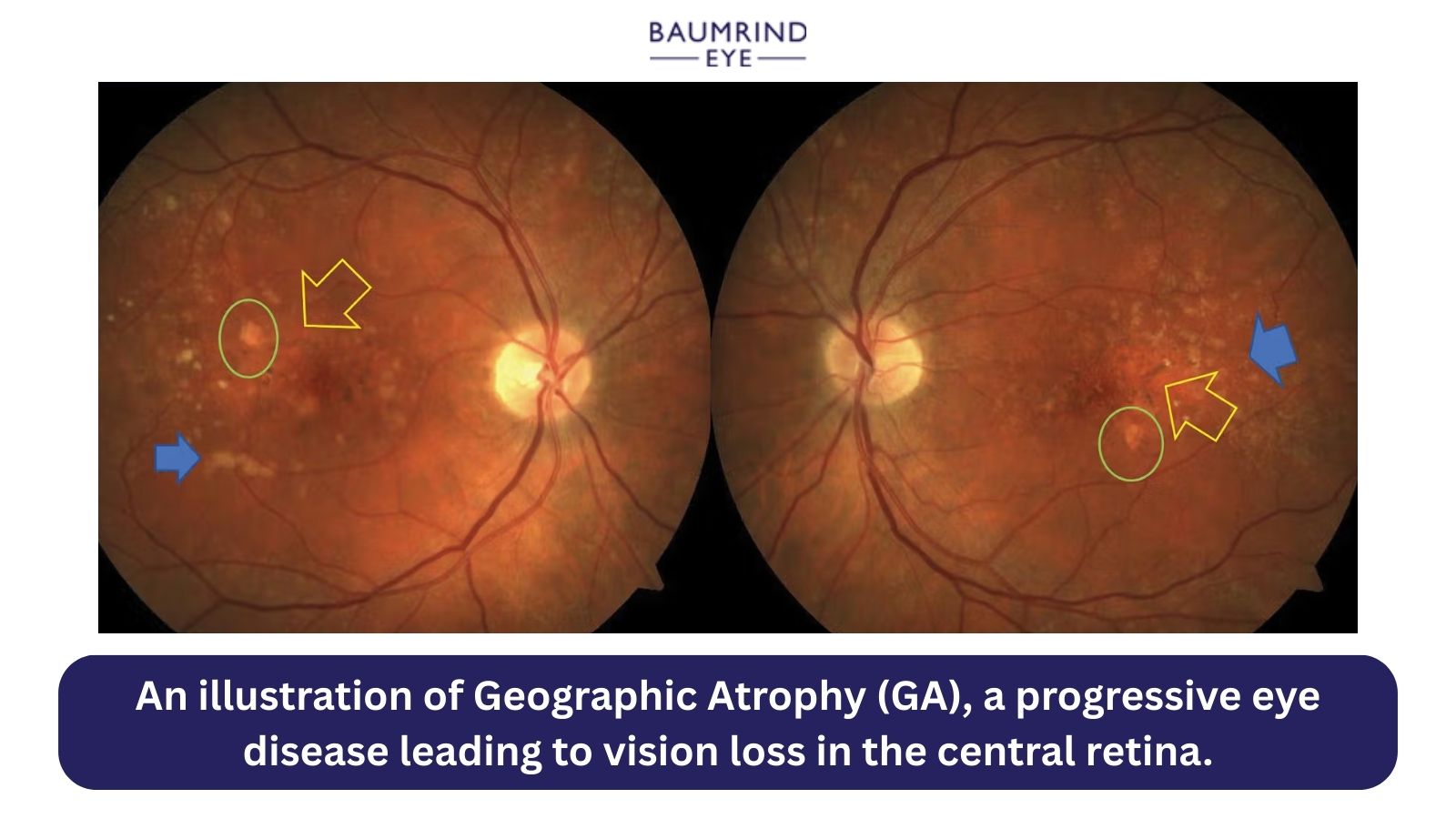

Geographic atrophy is the advanced stage of dry age-related macular degeneration, a common eye disease affecting the macula—the part of the retina responsible for acute, central vision. When you have GA eye disease, the macula starts to break down and create blind spots or dark spots in the middle of your vision. While your side (peripheral) vision is usually still intact, losing central vision can make everyday activities difficult.

This condition tends to occur in both eyes but can develop unevenly in each. Blind spots can grow in size over time, greatly affecting your quality of life. The silver lining: although geographic atrophy was once thought to be untreatable, new medications and management strategies are bringing hope to GA patients.

How Common is Geographic Atrophy?

Geographic atrophy is common. It occurs in over 8 million people worldwide, and it accounts for about 20% of all cases of age-related macular degeneration. In the United States alone, over 1 million people have GA eye disease. Older people, particularly those over 60 years, are likely to be affected by it, but some factors like genetics or lifestyle can make you prone to it.

Symptoms of Geographic Atrophy

The symptoms of geographic atrophy are slowly developing, and you may even not know you have them at first, particularly when you have unilateral involvement. With the worsening of the condition, you may experience:

- The blurring of vision: Objects can appear blurry or less distinct even with glasses.

- Challenges in daily activities: Reading, driving, sewing, or other activities based on central vision become more challenging.

- Blind spots: You may experience a gray or dark spot in the center of your vision, called a scotoma.

- Low light difficulty: Low-light settings, like restaurants, are hard to see in.

- Dull colors: Colors may seem less vibrant or faded.

Since these changes occur gradually, you might not realize you have GA eye disease until it is more advanced. The only way to catch it early is with regular eye exams.

Who are at the Risk

Anyone may develop geographic atrophy, but some factors enhance its risk. They include:

- Age: 60 years or older raises your risk.

- Ethnicity: White individuals are more likely to develop GA eye disease.

- Eye color: Light-colored eyes (blue or green) might raise your risk.

- Genetic history: If your relatives have had macular degeneration or other eye disease, you are more likely to be affected.

- Smoking: A history of or current smoking significantly raises your risk.

- Poor diet: Insufficient consumption of quantities of fruits and vegetables, especially dark leafy greens, is bad for the eyes.

- Sun exposure: Prolonged sun exposure without protection can be a causative factor.

- Medical conditions: Being overweight, having high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, or heart disease could increase your risk.

Vision problems, including the ability to see only 20/200 or poorer (much blurrier than the usual 20/20), also raise the risk of geographic atrophy.

Complications of Geographic Atrophy

The vision loss due to geographic atrophy is irreversible, which can complicate life. You might have difficulty with:

- Reading menus, books, or phone screens.

- Driving, particularly at night or in unknown areas.

- Identification of friends' or relatives' faces.

- Enjoying hobbies like knitting, painting, or puzzles.

While this is intimidating, it is possible to adjust and be independent, which we will address later.

Diagnosing Geographic Atrophy

If your eye specialist suspects geographic atrophy, they will start with a comprehensive eye test and ask you about your symptoms, medical history, and family history. They will also use special tests to diagnose it, including:

- Fundus autofluorescence: A form of retinal photography that signals damaged tissue without the application of dyes.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): A painless test that employs light to generate detailed pictures of your retina.

- Microperimetry: A test that maps your visual field to test for blind spots.

- Multifocal electroretinography: Measures how your retina responds to light.

These tests enable your physician to see how much damage has been caused and determine the best course of treatment for you.

Treating Geographic Atrophy: Is It Curable?

So far, geographic atrophy is not curable. However, there are some treatments that can delay its progression and potentially reduce the risk of vision loss.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved two new medications to slow its progression:

- Pegcetacoplan (SYFOVRE™): An injection given monthly or every other month to slow macular damage.

- Avacincaptad pegol (IZERVAY™): Yet another injection that helps in retarding the advancement of GA eye disease.

These drugs are inserted right into the eye itself by your eye doctor. Side effects can be eye irritation, bleeding in the back of the conjunctiva (the thin, clear layer over the white of your eye), floaters, or, in the very unlikely event, new vessel growth within the eye.

In addition to medications, your doctor will also prescribe:

Visual rehabilitation: Spectacles or magnification aids to enhance your eyesight.

AREDS2 supplements: These add antioxidants like lutein, zeaxanthin, vitamin E, and zinc to enhance eye function. (Warning: Do not take AREDS1 if you are a smoker since it contains beta-carotene, which in smokers is linked to lung cancer.)

Implantable mini telescope (IMT): Surgery where a compact device is put in your eye to replace the lens in your eye to enlarge images and route them to healthier regions of the retina.

Can You Prevent Geographic Atrophy?

There is no certainty to prevent geographic atrophy because it is an effect of macular degeneration, whose pathology is multifaceted. Still, you may reduce your risk by making healthful decisions:

- Stop smoking: If you are a smoker, quitting can save your eyes (and your health).

- Manage health conditions: Manage diabetes, high blood pressure, cholesterol, and weight.

- Wear sunglasses: Choose yellow-tinted sunglasses to shield your eyes from harmful UV rays.

- Eat well: Stock up on leafy greens, colorful fruits and vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acid-rich fish.

- Stay active: Exercise regularly to stay healthy overall, including your eyes.

When to See Your Eye Doctor

If you experience any change in your vision—like blurriness, blind spots of vision, or inability to see in the dark—contact your eye care specialist right away. Sudden vision loss or eye pain must be addressed immediately. Your eye care specialist will let you know how often you should schedule check-ups, usually every 6 to 12 months for follow-up.

Living with Geographic Atrophy

Living with geographic atrophy is not easy. But you are not alone. Your doctor can help you live your routine life with minimal discomfort. Reading and other activities can be done with the use of vision aids, such as magnifying glasses or large-print materials. You can join support groups or initiatives to share your experiences with other patients and stay motivated. By taking charge—keeping up with eye exams, doing what your doctor says, and making healthy lifestyle choices—you can manage GA eye disease and remain independent.